Editor’s note: Jordan Kretchmer is the founder of Livefyre, a realtime commenting and conversation platform for publishers and online communities. He doesn’t think much of Facebook comments. In this guest post, he explains why.

I’m not gonna lie, I hate Facebook Comments. It’s not just because it competes with my company’s product (though I’m sure that has something to do with it). It goes much deeper than that. And I am not alone.

Whether you’re a casual blogger or the owner of a major tech site like this one, it’s likely that you’ve recently begun to think a lot more about the comments system on your site.

Blog comments have been around since 1997 (or earlier, if you count Usenet, or various more primordial forms of online diary-keeping). But, never have comments been as important, or contested, as they are today, especially as Facebook charges into the space with its updated comment widget.

If you’re like us, you’re trying to keep up with the frequent reports from the field about which sites are switching to Facebook Comments (like TechCrunch) and what their respective communities think about it. The bulk of the debate centers on whether or not to replace Disqus with Facebook Comments, or the feature war that in almost all cases misses the point entirely.

I’m a bit biased, I admit, but I think we have to look beyond the feature-set of Facebook to grasp the impact that one line of javascript could have on a site’s community, and more importantly the entire web.

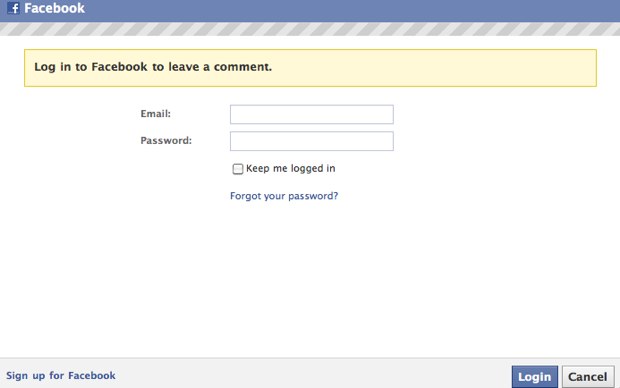

This post tries to unpack the many places where Facebook fails those who adopt the commenting platform as a cure-all to bring community back to their content. (And kudos to TechCrunch for not shying away from this debate. I hope you weigh in with your own thoughts in the comments below, even though you will have to log into Facebook to do so).

Facebook Ignores the Interest Graph

Facebook Comments approaches online identity and discussion from a perspective that doesn’t (and won’t) align with the interests of publishers or commenters.

Conversations around the web are built on the interest graph, not the social graph. By making the assumption that I want my 800 Facebook friends in every conversation I participate in online, it forces me to combine all of my interest groups and all of my friend groups into one giant bucket. While that social segmentation worked for my college Facebook network back in the day, it broke down the day my mom could join that network, along with my sister’s friends and the guy that beat me up in middle school.

I can choose who I include in different discussions in real life. Why shouldn’t I have that control on the web too? What happens, and this has been proven out on numerous sites, is that interaction rates drop dramatically when Facebook comments get installed.

The issue of conversation context is related to this, and deserves a post on its own. Suffice it to say that personal comments from private Facebook pages don’t make sense in the context of a conversation on a publisher site. This random comment intrusion damages the value and quality of conversations by reducing commentary to one-line personal banter between two or three friends.

It also goes the other way around; random comments appearing unbeknownst in your Facebook feed will confuse more than it will engage others. While Facebook allows you to opt out of that, it’s checked by default, and the option to deselect it isn’t even presented to you on replies to comments. Sneaky tactic.

Facebook Over-Prioritizes Silencing Trolls

Facebook Comments hones in on trolling by forcing real identity, but the end result isn’t just the silencing of trolls, it’s the silencing of everyone. If you’ve followed the interminable trolls versus no trolls debate, you know exactly what this means. Anonymous commenters are lumped into the all-encompassing evil troll bucket.

But the truth is that there are good trolls, and there are bad ones. The good ones spark engaging dialogue and encourage the development of amazing content. We have to find the balance between utter silence, and allowing for important contribution. One thing is for sure, using Facebook Comments to kill trolls is like trying to kill a fly with a boulder. The result will be way more destructive than just letting the fly buzz around and eventually, go away.

Facebook Wants Your Data. Badly.

Publishers who have chosen to hand over their entire communities to Facebook are likewise choosing to give up the entire value of their community. What this means is that they no longer have any data on loyal commenters, and no email addresses, which means no ability to communicate with them again. They’re no longer your users, they’re Facebook’s.

You’re giving a huge strategic and valuable asset to Facebook. They understand the inherent value of comments and community, and are attempting to take it out from underneath publishers before they even realize what’s happened. And we’re back to where we started—publishers don’t quite understand the value of their communities yet.

Why not just redirect www.beta.techcrunch.com to www.facebook/techcrunch then?

Any publisher would find that absurd, because they know for sure that their content has value—and they’ll never hand that over to anyone else.

Don’t Throw in the Towel

As a publisher or blogger of any size, creating an active and engaged community isn’t something that you have to do alone. There are plenty of companies building tools that foster better conversations. Just remember that focusing on the people in your community will make your site more valuable, without giving that community away to Facebook.