Inventor: Paul Allen

Filed: August 27, 2010

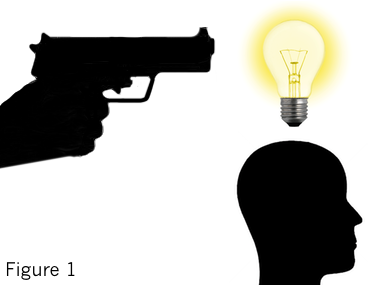

Abstract: A method for preventing innovation, specifically in the tech sector, by way of a dangerous misconception of what is patentable and a sadly overtaxed intellectual property regulatory system.

Summary of the Invention: During a period of change and invention, ideas may occur to a person, and a few possible ways of manifesting those ideas. By instantly submitting a patent request, the person can secure as their own property not only the methods they have actually invented, but all possible derivatives and independent creations resembling said methods. After waiting a suitable period of time, during which the entire landscape of the industry may change, the patent holder then can exchange these patents for riches, while simultaneously nullifying the gains of a decentralized, idea-powered economy.

There are so many things wrong with Paul Allen’s reprehensible and baffling lawsuit that we might do better by trying to figure out what he’s doing right, and then condemn what remains.

Take a look at the patents:

6,263,507: Browser for Use in Navigating a Body of Information, With Particular Application to Browsing Information Represented By Audiovisual Data.

6,034,652 & 6,788,314: Attention Manager for Occupying the Peripheral Attention of a Person in the Vicinity of a Display Device.

6,757,682: Alerting Users to Items of Current Interest.

Really, at least give them a good once-over. Because they certainly aren’t without merit. The 507 patent, filed for in 1999, is forward-thinking and acknowledges the need (then not particularly pressing) for obtaining samples or a summary of far more information than one could possibly review by simply browsing it. And the 682 patent, from 2000, is right on in suggesting the need for more or less real-time notifications showing items related the user’s interest.

The patents provide some specific implementations of these ideas — good ideas, too. And those implementations should be protected by law, since they are essentially machines invented part and whole by the filer. But the step taken by Allen today and similar steps taken by others in recent years indicate a deliberately overreaching interpretation of what exactly they have been granted rights to.

Here’s a revealing excerpt, from page 16 of patent 682:

It should be appreciated that the present invention can be implemented in numerous ways, including as a process, an apparatus, a system, a device, a method, or a computer readable medium such as a computer readable storage medium or a computer network wherein program instructions are sent over optical or electronic communication links. Several inventive embodiments of the present invention are described below.

Well, well! Apparently they are filing for several patents here. The invention itself, some “inventive embodiments” of that invention, and all possible embodiments of that invention, which they lay claim to simply by suggesting that such and such an embodiment could potentially exist.

Please permit me a slight digression.

A long, long time ago, humans lived in darkness because jealous Zeus had hidden the secret of fire from them. Prometheus felt bad for the men, so he smuggled a spark to them inside a fennel stalk. Zeus found out about this, and to this day (or so they say) Prometheus is chained to a rock, having his liver torn out daily by an eagle. I like to consider this the first intellectual property dispute.

Paul Allen has appointed himself Zeus in this situation, and is getting ready to chain Google, Facebook, Apple et al. to the rock of infringement, with his crack team of eagles extracting damages from them day after day.

The trouble is, the tale is allegorical, and when you look at it this way, the trouble with Allen’s (and everyone else’s) disputes becomes plain. Prometheus (“forethought”) isn’t just some guy — he’s the embodiment of original thought and invention. Fire didn’t literally get smuggled to us in a straw. The story describes how human ingenuity produced that which the powers that be didn’t want us to have.

This is all just a monstrously roundabout way (I never could resist a classical allusion) of saying that you can’t patent an idea. I mean, it’s elementary: even if you were to be the first to have it, there is nothing stopping another person from having the same idea occur to them independently. Consider perhaps the most famous example, in which Marconi patented a number of things related to radio transmission, despite Tesla and others having demonstrated them years earlier. The court said some years later, after a number of conflicts:

Marconi’s reputation as the man who first achieved successful radio transmission rests on his original patent, which became reissue No. 11,913, and which is not here in question. That reputation, however well-deserved, does not entitle him to a patent for every later improvement which he claims in the radio field.

Sounds a little bit like what would happen a century after that momentous invention. In the early 2000s, companies taking advantage of the internet were sprouting like weeds, and I guarantee that there was an enormous overlap in the ideas they had for how to display their information, navigate and parse large stores of data, and so on. How could there not be?

If patents granted exclusivity on the scope Allen and his firm think they do, then Marconi wouldn’t have applied for a patent for his method of radio transmission. He would have patented the idea of a box that can communicate with another box, and provided a few possible methods — “in this embodiment of the invention, radio waves.” Someone would have patented “an invention in which people are propelled by a mechanism with wheels.” And as long as we’re at it, why not patent a way of applying for and exploiting the patent process in the way I’ve suggested above? It’s like building something out of LEGO and then patenting LEGO.

“We recognize that innovation has a value, and patents are the way to protect that,” said one Mr. Postman, spokesman for Interval Research Corporation, Allen’s instrument in this drama. To be sure! Unfortunately, the patenting process, as we’ve suggested on this site before, is grossly inappropriate for the current generation of software (and software-like) innovations. Not that the process to blame, exactly: it was just made with a different time scale and invention category in mind. The USPTO says:

Utility patents may be granted to anyone who invents or discovers any new and useful process, machine, article of manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof

The idea of a process is not a process. The concept of a machine is not a machine. Patents are granted to protect real things — things which are in danger of being stolen or duplicated. Algorithms, code, exact layouts, specific methods, these are things which deserve patent and should be protected, because they are the informational equivalent of actual manufactured machines and parts. But the underlying ideas for the machines and parts are not protected, firstly because that would prevent anyone from creating “useful improvements thereof,” and secondly because, as we have observed throughout history, it’s rare that you’re the only one with that idea.

If Allen were suing just Facebook, or just Google, for this or that specific infringement, one might be able to look at the patents’ claims and say “yes, it seems that Google really did replicate this invention rather than creating something new.” But he’s suing all of these companies for the exact same thing, or (as would probably have to be proven in court) slight variations on the theme. He’s suing them for having the same idea as someone else.

It may be that I’m going off half-cocked here (in addition to simplifying things, the better to editorialize), and perhaps it will transpire that all these companies are in fact using some piece of Vulcan-owned property without permission. But I seriously doubt that; over ten years, even an exact replica of the methods described in these patents would have undergone such changes as to make it a totally different “machine.” Furthermore, while it may be legal to do so, strictly speaking, don’t you think it’s rather arbitrary and opportunistic for Allen et al. to pursue these patents now, having waited years since they were granted, letting innovations and products arise as fresh targets for litigation, thinking themselves safe from legal predation?

I also doubt this will be adequately handled by the courts, either. Imagine representatives from a dozen high profile tech companies all arguing on different levels against this or that implementation of something the judge has no idea about, and Allen’s team stolidly pointing at a patent clearly granted, yet just as clearly ridiculous to anyone with eyes to see. I’d rather eat glass than preside over such fruitless pageantry.

Could this be a blessing in disguise? I hope (against all odds) that this case gets swiftly and decisively struck down and becomes a useful precedent and bulwark against future patent trolling. That’s a practical deterrent, and as much as patent law needs serious reform, we have to work within the system for the time being. Unfortunately, it’s far more likely that it will drag on and come to a meaningless resolution in a year or more, when the industry will have moved on yet again and the decision rendered doubly moot (if not moot ten times over by now).

This is an excellent way to cancel out the goodwill Allen may have generated by pledging to donate much of his fortune to charity. Everything about this lawsuit breathes greed and obstructionism — not that he’s acting alone, or the only guilty party, but this is certainly a very high-profile and characteristic demonstration of the troubled nature of intellectual property in this country. Luckily for us, the real innovators don’t let this kind of petty meddling get them down.