![JOKES and WISECRACKS [ORIGINAL] - gnat](https://techcrunch.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/jokes-and-wisecracks-original-gnat.gif) Andy Sjarif has an almost weird, man-crush on Google. No matter what crazy things Eric Schmidt may promise shareholders, Sjarif is in no doubt that the great and mighty Google can achieve them. Self-driving cars? Trips to the moon? Wind farms? All in a day’s work at the Googleplex. Google with its execution, its Ph.Ds and its algorithms is Sjarif’s mahaguru.

Andy Sjarif has an almost weird, man-crush on Google. No matter what crazy things Eric Schmidt may promise shareholders, Sjarif is in no doubt that the great and mighty Google can achieve them. Self-driving cars? Trips to the moon? Wind farms? All in a day’s work at the Googleplex. Google with its execution, its Ph.Ds and its algorithms is Sjarif’s mahaguru.

But – all that said – he still wants to slaughter them in the Indonesian market.

To that end, his company Sitti has indexed more than 20 terabytes of data; comprising 12 million articles, 12 million Twitter accounts, 800 million pages of websites and blogs, 10 million Facebook conversations, 20 thousand words of slang and 2.7 billion Google search terms– all in Bahasa Indonesia and all to make mathematical sense of Bahasa language context, so that it can match ads to content better than Google.

Google has been supporting an Indonesian language version of Chrome for a few months, but it only launched Adwords and announced it was ready to serve the market October 8… about a week after Sitti just launched a trial of its contextual ad engine consisting of that consisted of 2,700 individual ads for 529 brands. It must be doing something right; not only did Google come into the market almost immediately but, the day after the campaign launched, Google bought the keyword in Bahasa for “Sitti.” See the screenshot, grabbed by Sjarif below.

A few weeks later, Google sent a team to Indonesia and held dozens of job interviews. Sjarif claims a few candidates were told that Google was going to crush the small upstart. They are said to be hiring a local team of about a dozen employees in 2011.

Of course, the timing could all be coincidence. Indonesia is a hot market that, as I’ve argued before, only a fool would completely ignore. But, if nothing else, it certainly makes Sitti look good to the locals. There’s that nationalistic pride issue of Google making more than anyone else when it comes to Indonesian Web advertising, but not employing many locals and not paying much in local taxes. Sitti is undoubtably a gnat in the Google universe. But every once in a while, a gnat gets your attention and you swat at it, right?

Whether he helped provoke it or not, Sjarif is thrilled Google is coming into the market, because he thinks it’ll drive more professionalism, attention and revenues for the ecosystem as a whole. Google Adsense tailored for Indonesia means local Web companies can better bootstrap companies with Google ads, the way the early Web 2.0 wave of companies in the United States did. The two could co-exist the same way mass players like Google and more tailored ad networks like Federated Media did for US startups.

Google brings heft to the market, but it will never get as deep into the nuances Bahasa indexing as Sitti is. Sitti cites the example of ZAO Begun in Russia, which Google tried to buy for $140 million before it was blocked by the Russian government, as evidence that language can be a powerful differentiator on the Web.

More than a year ago, Sjarif tried to raise funding from Valley VCs and one very well-heeled one he asked me not to name said, “It’s not that your technology isn’t hot, it’s the fact that you’re here. In the Valley, people would be fighting over you.” So Sitti raised money from a handful of local angels instead. They were offline moguls who didn’t know a thing about the Web, but backed him anyway. This is a running theme among Jakarta Web companies I met this past trip. Knowing the big families is important as entrepreneurs shape a new industry in a country with infrastructure issues and little local venture capital. One of these angels called him the day after he committed the money and said, “Andy, do two things for me. The first is don’t die, because this is going to be big. Now, explain to me what you do.”

Indonesians complain about a lack of sophisticated Web expertise and mentorship, but it’s one of the only emerging markets where I don’t hear complaints about a dearth of angel money. Sitti’s angels have given the company a long leash, deep pockets and helped open doors to the country’s old media elite. Sjarif now turns down traditional venture firm money, bootstrapping the company’s growth by giving big brands local media consulting advice for digital campaigns. “I want to talk to VCs when I don’t need their money,” he says. Smart plan. Venture money can come and go quickly in markets that don’t have a track record of returns.

But back to the product. Sjarif is so deep into how, when, where and what Indonesians say on the Web that he can tell you a lot about this phenomenon. He says three things drive the Indonesians love affair with Tweeting and Foursquare for instance: They’re narcassists; they love to gossip about one another (more than celebrities, unlike the US) and they get bored during urban traffic jams. He says he can map the traffic flows in Jakarta based on the volume of Tweets he indexes at any given time.

Here’s a visualization Sitti did of part of my Bahasan Twitter connections, created in part to embarrass me at an event. In true polite Indonesian style there was little embarrassing on it, except for the fact that ARRINGTON is the biggest hub on this map. And, what the hell is Mashable even doing on there? I might get fired for that if the big yellow dot ARRINGTON sees it. Interesting that @katharnavas in India is the same size dot as @arrington. Thanks for the links, whoever you are. The yellow dots are my connections; the red dots are connections to them or connections with smaller networks that have mentioned me; and the size of the dot indicates how frequently.

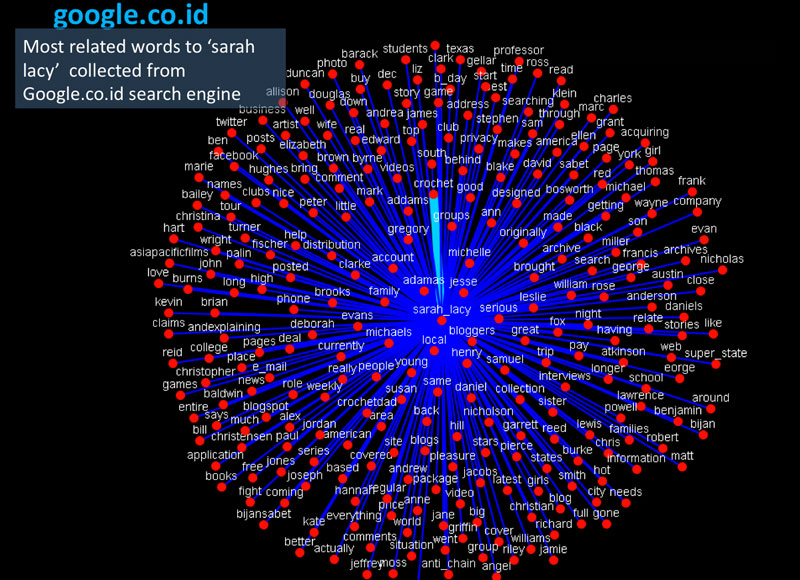

And this is a relation of most common words associated with “Sarah Lacy” into Google.co.id’s engine:

It’s certainly different than the words most related to me in an English-language search. It seems in Indonesia, haters don’t gotta hate quite as much. Good to know. The company also did a visualization of topics on my personal blog and conversations over Twitter they’ve indexed that relate to me.

Sitti wasn’t the only company I met trying to build a business out of social media sentiment in markets that were ignored by companies like Google up until recently. There are several companies in Asia generally seeking to make sense out of the wave of pages being created on the Web in Asian languages in order to turn all that traffic into actual cash. Since, most of those pages are being created over social media, it takes a company that can understand slang, context, and meaning in just 140 characters. And a lot of these companies put the Valley’s self-proclaimed “social media consultants” to shame with highly scientific and proprietary approaches.

Two very different examples are Brandtology in Singapore and Scraplr in Indonesia. Brandtology promises to make better sense of what social media is saying about a brand by hiring an army of smart college grads to sit and parse queries so the machines don’t mis-read things like sarcasm and local slang. While, I’m sympathetic to the idea that there are certain things an algorithm doesn’t get, the economics of this company didn’t quite sense, and didn’t quite hold up the more questions I asked. How do you hire enough college-educated locals to filter all those keywords and still have a cost-effective solution? The answer is it’s not a free product. It costs between $1,000 and $10,000 a month depending on what percentage of keywords you want examined. Without paying extra, you don’t really get better relevance. I’m not sure that scales as the cost of talent rises.

Scraplr takes a totally algorithmic approach, that is specifically tailored to Bahasa, not emerging market languages broadly. Because it takes a machine-only approach it has a freemium model. That means more people can see how good the site is, but making money will be a bigger challenge. There is probably room for all three, as long as they perform as advertised. Indonesia and social media are both black boxes the West is struggling to understand.