Bing Gordon is a partner at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, where he led the firm’s investments in Zynga (where he serves as Operating Director), Lockerz, and ngmoco. Bing was Chief Creative Officer of Electronic Arts from 1998 to 2008, after heading EA marketing and product development off and on since EA’s founding in 1982. He helped write the founding business plan that attracted Kleiner Perkins as an initial investor. Bing contributed design and marketing on many EA franchises including John Madden Football, The Sims, Sim City, Need for Speed, Tiger Woods Golf, Club Pogo and Command and Conquer. Bing has also been a director at Amazon since 2003, and held the game industry’s first endowed chair in game design, at USC School of Cinematic Arts. He is a trustee of the Urban School of San Francisco. Bing’s favorite games of all time are World of Warcraft, the Sims, Diablo, Pogo, Civilization, Columns, Freecell, Farmville and Mafia Wars.

Bing Gordon is a partner at Kleiner Perkins Caufield & Byers, where he led the firm’s investments in Zynga (where he serves as Operating Director), Lockerz, and ngmoco. Bing was Chief Creative Officer of Electronic Arts from 1998 to 2008, after heading EA marketing and product development off and on since EA’s founding in 1982. He helped write the founding business plan that attracted Kleiner Perkins as an initial investor. Bing contributed design and marketing on many EA franchises including John Madden Football, The Sims, Sim City, Need for Speed, Tiger Woods Golf, Club Pogo and Command and Conquer. Bing has also been a director at Amazon since 2003, and held the game industry’s first endowed chair in game design, at USC School of Cinematic Arts. He is a trustee of the Urban School of San Francisco. Bing’s favorite games of all time are World of Warcraft, the Sims, Diablo, Pogo, Civilization, Columns, Freecell, Farmville and Mafia Wars.

I worked at Intel in the late 70’s, and saw the Moore’s Law business strategy firsthand. Intel’s business depended on launching ever more powerful microprocessors, and charging high profit margins at the beginning of each technology life cycle, before competitors could “second-source” designs, and slice margins wafer thin. For the next 3 decades, Intel became the world-leader in microprocessors, the clock of Silicon Valley, by relentlessly investing in new fabrication facilities and new designs against their belief that Moore’s Law holds true.

I met Gordon Moore in 2005, and asked him to predict how much longer his Law would hold. After all, who should know better? Mr. Moore answered, “I never actually thought of it as a law, more as an observation to bet on.” He liked building big factories, and the “law” justified the next chip fabrication plant. “And today? I have no idea. But I just asked Otellini (Intel CEO at the time), and he told me he just approved another billion dollar fab, so it better last a couple more years.”

The Vision

Moore’s Law was baked deeply into the founding strategy of Electronic Arts. We assumed that computers like Atari 800 would win over the Atari VCS, that floppy disks holding 140k of memory would win over tape cassettes, and that one day computers would be able to power lifelike graphics to compete with filmed movies. “We see farther”, we crowed. We predicted the games business would develop to stand side by side with the $20 billion annual revenues of movies and recorded music. We foresaw a day when a New Hollywood would be created by “software artists” who harnessed Moore’s Law into a new category of art. We believed that their digital games would one day deliver the kind of emotional experiences we all enjoy in movies, what Stephen Spielberg describes as “sitting back and being washed over with emotion.”

We tried to capture this vision in the 1983 launch ad for Electronic Arts. “Can a computer make you cry? Software worthy of the minds that use it. Toward a language of dreams. Join us…we see farther.” Heady stuff. And this at a time when games were sold in baggies in mom and pop computer stores like the Byte Shop, and a third of the cassettes didn’t run when you got them home.

As we now know, the business vision came true! The games industry grew to rival the movie business (although it’s a business of DVD’s instead of popcorn now). Games grew to be bigger than music (not as impressive as we once thought it would be). Game designers like Miyamoto, Will Wright, Sid Meier, John Carmack, Brian Reynolds, stand as tall as standout leaders in traditional media, like John Lasseter, Tina Fey or J.J.Abrams.

We created an industry with tens of thousands of jobs that attracted refugees from the movies and animation, from board games and boring jobs. University programs graduate hundreds of trained game devs every year. And when “killer apps” launched in the first year of a new hardware platform, profits were predictably generated, dramatically more consistently than in any other creative business, reminiscent of the Intel life cycle technology model.

Some of our satisfaction came from overcoming the disbelievers. After the crash of the initial Atari VCS business in 1983 and the massive returns of the terrible E.T. game, “experts” likened videogames to the hula hoop, just another short-lived fad. Electronic Arts went public in 1989, after 16 consecutive quarters of profits, on respectable sales of $72 Million, at a valuation of $80 Million, and then the stock went down! As one industry insider said ironically and somewhat bitterly, “Videogames are the Rodney Dangerfield of entertainment…we get no respect.”

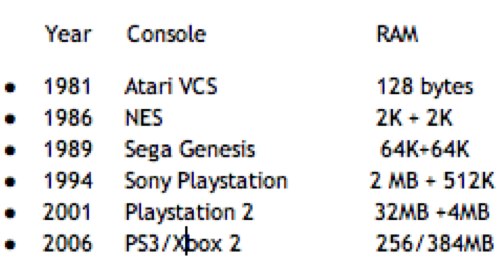

Moore’s Law drove the train of successes and profits for our industry, enabling the launch of successive “next gen” platforms like clockwork, with almost exactly 10x RAM and 10x graphic power, every 5-6 years from 1981 to 2006. But we fell short of the lofty creative goal of “Can a Computer Make You Cry?” because we didn’t develop new models of character and narrative. Floyd, the robot friend in Steve Meretsky’s Planetfall, was a heart-warming sidekick but, no matter what words we typed into the Infocom parser, he died a sacrificial, text-only, death for us. Leisure Suit Larry gave us smarmy shortcomings to remember, and Lara Croft made it safe for boys to play female characters. But the emotional connection of the best videogames never consistently delivered the “New Hollywood” experience we envisioned. Critics kept repeating, “Yes, but” to our success, because, well, they couldn’t see a Scarlet O’Hara or a Titanic or a Precious in our body of work.

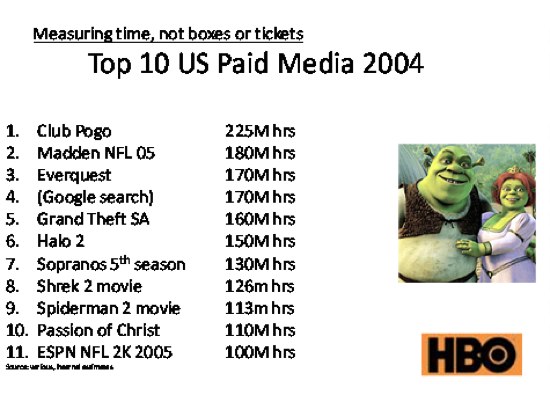

Stickier than Hollywood

While we were looking for New Hollywood powered by Moore’s Law, we were actually creating a new kind of play that is the most engaging form of media in history. Here is a chart I built in 2005 ranking paid entertainments on hours of usage, rather than box sales. Even before WOW, games represented the Top 5 ranks for hours of usage for paid entertainments, and now World of Warcraft garners 4 or 5 times as many hours as #1 did in 2004. (There has never been a commercial entertainment that has been “stickier”, created more hours of usage in a given year, than World of Warcraft.) Way ahead of any movies, TV, music or books. But our industry had Hollywood envy and saw the world through the lens of Moore’s Law, and so we missed the importance of what we had become.

From Moore’s Law to Mother-in-Law

After Facebook, Wii and iPhone won my family Christmas several years in a row, I did some game-maker soul-searching. I recounted my own favorite game memories, and found that they looked more like Facebook newsfeeds than like the game commercials and screen shots we communicated to customers and our dev teams. In my mind’s eye, each favorite gaming moment has a profile picture of a person, and a feed of a game moment. Game memories weren’t anchored in Moore’s Law, but “Mother-in-Law”. It didn’t take more pixels, faster framerate and new game mechanics, but stories told by people I cared about. For me, game moments are like a vacation photo album; they seem dull without people in the pictures.

Avatars, profiles, state machines, tech trees, collections, sliders and interface toys are the kinds of masterful game mechanics and structures that the software artists of the Moore’s Law generation invented and perfected. For two decades, we imagined that these mechanics would leverage the price/performance breatkthroughs of Moore’s Law to create new kinds of movies. But, in retrospect, we were misguided. We were looking for emotion in all the wrong places.

Golden moments of gaming

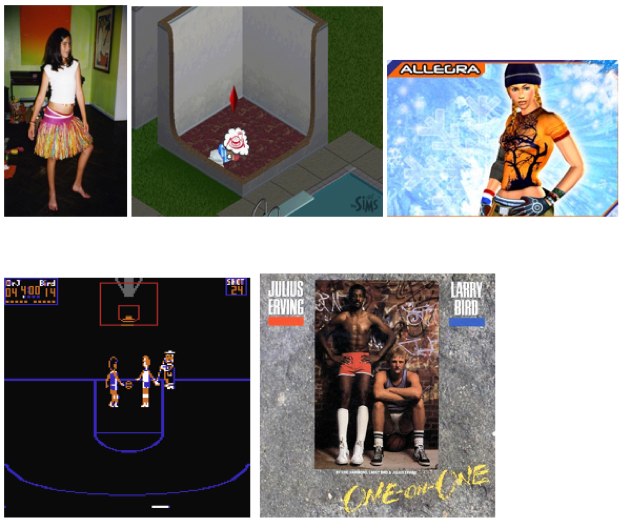

One December day in 1999, I got jolted to my core. My daughters, Chloe and Allegra, were playing a pre-release version of The Sims, all sitting in a single swivel chair with their best friend. They alternated play, 10 minutes at a time. Since one player’s Sim was another player’s NPC, they had fun watching each other’s Sims come and go from the houses they were building. Just after I snuck out to wrap presents, there came a blood-curdling scream: “Daddy, Zelda killed my Mommy! Aaaooowww!” For an amygdala gland moment, I ran. Allegra, fell into my arms, sobbing. But there was no dead Mom on the floor, only a dead sim. Allegra’s friend, playing a house with a single female, hadn’t been able to prosper with a solo household, didn’t want to restart, so had tried to win a mate by macking with one cute guy, who was Allegra’s “dad”. The jealous wife started a cat fight, so when she went to relieve her bladder need, Allegra’s friend switched to build mode, bricked up the bathroom door, until the “mom” croaked. This seemed hilarious, but Allegra hadn’t appreciated that the simulation was global. When it was her turn to play, her house had a lonesome dad and a tombstone in the backyard. Cue the piteous wail! As the adrenaline slowed, it occurred to me that, “Yes, a computer can make you cry,” and then, “Sims is going to be bigger than even we thought.”

In all the years of celebrity game-makers, there was only one moment that mattered to me, and that was with Julius Irving. The legendary Dr. J. came to the San Mateo YMCA, where the 30 or so EA employees tried to convince him to endorse a game to be published by some earnest kids with big ideas, small revenues, and bricks for free throws. He had huge but articulate hands, and amazing grasp of his stats from every square foot on the floor. He shared his philosophy about hot streaks, that “your teammates give you the right to miss a shot.” And he inspired developer Eric Hammond to do 6 extra iterations on the animations, including a “finger roll” that customers thought was photo-realistic, and a cute janitor who swept the glass off the floor when J or Bird shattered the backboard. When we asked, what would actually happen in a real 1 on 1 contest with the much taller Larry Bird, the Doctor answered, “I’d like to believe I could beat Larry 10 times out of ten.”

The Videogamification of Everything

When I predicted “the videogamification of everything,” I was still depending on Moore’s Law to drive the manifest destiny of gaming. I expected game interfaces and habits would change product design, advertising, communications and eventually education. But it’s Mother-in-Law, not Moore’s Law, that is making this prediction come true. iPhone proved that, with 70 percent of downloads being games, making Touch“the funnest iPod ever” enabling publishers like ngmoco. Zynga and other publishers on social networks proved the ability to reach daily audience sizes that I, for one, never imagined possible. Location-based apps like MyTown overlay your friends on real places like clubs and libraries, not just in the fraternity houses that drove the success of Madden Football. When your golden game memories look like a Facebook feed, it is no wonder that social networks can expand the emotional frontiers and audience appeal of gaming.

Social networks also amplify the productivity of gaming, in a surprising way. One of the reasons audiences have expanded so rapidly is a social effect called “the power of weak ties.” People find spouses, new jobs and new ideas, not from their very best friends, but from friends of friends. Because games are so much fun, so sticky, they can build and maintain bonds with former classmates or co-workers, without having to do something cringey, like attend a class reunion. Games create shared goals.

BBC News Magazine recently cited a study that found the more friends you have, the more you earn. But modern life can allow little time to maintain meaningful relationships, so what’s the optimum number of friends? A study of 10,000 US students over a period of 35 years suggests the wealthiest people are those that had the most friends at school. Each extra school friend added 2% to the salary.

Since the rise of cities and the invention of the telephone, sociologists believe that the average person has 150 active friends. British anthropologist Robin Dunbar thinks this “Dunbar number” is limited by the size of our neocortex, and the friction of social obligation. But that was before Generation Z learned to text while driving, listen to music while studying, and keep friends forever on social networks. Most of the “with it” college students I meet these days have 500+ Facebook“friends”, and they aren’t even looking for jobs on Linked-in yet! I think 500 will be the new Dunbar number, as social software becomes ubiquitous, but it might be renamed the “Zuck number.”

Entertainment as a service

The future of gaming must be untethered from client side chips, and go for the biggest social potential. Social networks on the web and on mobile are activating a billion users, not just the hundreds of millions we had settled on for the traditional videogame business. As Scott Forstall of Apple once commented on the videogame market, “10 million sellers are just a niche to us. A billion users, now that’s a market.”

The next generation of game platforms have already arrived, and, apologies to Gordon Moore, they don’t require 10x transistor density. Instead, they depend on the cloud, the App store, API’s and frictionless availability of your social circles. Platforms are going virtual, and our industry must develop new skill sets, beyond those we fine-tuned in the era of Moore’s Law gaming. We must adopt a discipline of constant a/b testing, running hundreds of simultaneous tests per day, rather than several focus groups per month. Game-makers must all learn to channel Google.

In the Mother-in-Law era, the mantra for success is, “Reach-Retention-Revenue”. We will find new killer app categories like farming and aquarium management, to reach busy people with charming newsfeed messages like,“Your friend just sent you a lonely cow” instead of challenges like “You are not ready.” We are reaching the multitudes of people who want to co-operate and gift, not just compete.

The new currency is Daily Active Users, not metacritic score and NPD point of sale results of the last generation. Retention will be measured each day, rather than each year. The new magic numbers, instead of 90 metacritic score, are 40 million MAU’s, 30% engagement, 3 cents/DAU, and tipping point numbers like 15 friends on Facebook, or 10 followers on Twitter.

And revenue? Free is the new price, not $50. Instead of pre-selling, we build emotionally committed users before we ask some of them to buy from us. After learning to love Wal*Mart and FNAC and Gamestop in the last generation, we have to make Paypal our new best friend.

The future’s so bright, we gotta wear shades

With so much change, the future of gaming is bright. The generation rising craves what we know how to do, but only if we fit their lifestyle needs. They want short sessions. They want entertainment that lets them socialize, learn, have fun all at the same time, maybe even while trying to work out or study. They want their world to be clickable everywhere. They want to live their lives with achievement systems as fine-tuned as World of Warcraft, with power-ups for cooperating in structures like parties and guilds. They want us to help them bring play back into their work and education.

We can rise to the challenge.

The End of Moore’s Law

For 25 years, the videogame business has counted on Moore’s Law to deliver the promised land of the New Hollywood. We thought more powerful chipsets driving higher resolution pictures, more lifelike animations and bigger production budgets would almost automatically deliver the emotion of movies. We thought that amazing hardware would spontaneously generate resonant characters and heart-wrenching stories, but the highest points turned out to be a robot, a polygonal babe, and a horny swinger wearing a gold medallion.

But while we were looking for movies powered by millions of transistors, we ignored the emotions we were creating in games as a new kind of playground. Instead of creating emotion-laden, but passive stories, we elicited emotional moments off the screen, between friends, in the retelling, in the trash-talking. The emotional moments turned out NOT to have correlation with processing power, visual effects, and 3d graphics. The emotion came from who we played with, not what machine we played on. Games help us create richer photo albums of our lives.

So rather than trying to create stories and characters that “wash over” our audience, rather than trying to prove that a computer can make you cry, let’s create play spaces that help us make more and better friends. We are the characters, the heroes, the actors. And we are making stories together. More friends, not Moore’s Law.

Postscript

I had a pretty cool gaming moment recently. I found my high school daughter, always in the habit of dragging herself out of bed 15 minutes before her first class at 8:10, eating cereal at 6:30 one morning. Allegra, is there something wrong? I asked. “No, Daddy,” she said. “I set my alarm so my sugar cane wouldn’t wither. Oh, and I sent you the nails you asked for.”