I’m hardly the first person to have had the idea: I’m going to shut down my Twitter account.

I’m hardly the first person to have had the idea: I’m going to shut down my Twitter account.

I’m probably not the first to have decided to delete Facebook, Foursquare, Blippy, Google Buzz, LinkedIn or Delicious either. I may be the only person this year to have deleted my Friendfeed account, but only because I’m probably the only person this year to remember that he has a Friendfeed account.

No, I would hardly be the first person to decide to embark on a Social Shutdown (as Blippy’s Philip Kaplan termed it) having grown tired of the relentless look-at-me-ism of the Status Update Generation. And I wouldn’t be the first to realise that there’s more to life than feeding the insatiable blood-eating plant of social media – imagine Audrey II in Little Shop Of Horrors – just to keep the fifteen people who care appraised of my every move.

But that’s not why I’m doing it. Quite the opposite in fact: I may be the first person to decide to close down most of my social media accounts for purely narcissistic reasons.

Huh?

What?

Well. This might be news to people who only know me via Twitter, or who assume I write these columns just for the good of my health – but I actually get paid to do this shit. Specifically, I get paid no small amount of money to write about myself: or about technology, or whatever takes my fancy, as seen through the lens of my own experiences. Twice a week I do this for TechCrunch. Less regularly I do it for my publisher: my second memoir-style book, about my adventures living in hotels, will be published in a couple of months.

Narcissism, then, is my stock in trade. The moment people stop being interested in what I do, or what I think about things, then I have no career.

For that reason, I have embraced social media wholeheartedly. I’ve looked at bona fide celebrities of the age – Lady Gaga, Ashton Kutcher, Justin Bieber – and I’ve admired how they used Twitter and Facebook and Myspace and the rest to connect directly with the people who buy their music, their DVD’s, their whatever it is Justin Bieber produces. I’ve understood that if I want to build – and keep – an audience, then I have to do the same. I have to tweet every meal, photograph every date, create a fanpage on Facebook (actually, I could never quite bring myself to do that one) and I even have to share my credit card purchases on Blippy.

My publisher understood this too: as I was finishing my last book, they sent me a cheque to encourage me to bulk out my blog and create a social media strategy: safe in the knowledge that any increased awareness of my life would, by extension, lead to increased awareness of my book. It sort-of worked too: it was the blog that got me my most recent gig at the Guardian, which in turn lead to me writing for TechCrunch, where I take obvious delight in plugging the book at every possible juncture. Score one for social media.

As I shared more, though, I started to notice a funny thing happening. Rather than people becoming more fascinated by my life; the exact opposite occurred. “I loved your book, so I started following you on Twitter” people would tell me at parties. And then their expression would change: “your real life isn’t as interesting as you sound in print.”

“No shit”, I’d feel like replying. That last book took me a year to write and spanned almost ten years of my life, distilled down into just shy of 300 pages. Included were the drunken fuck-ups, the disastrous relationships, the business failures, the nights in prison cells, but consciously edited out were the boring parts: what I had for dinner on any given day, the uneventful dates, the minor successes and occasional parking tickets.

Whatever the excuse, though, the result is the same: people who enjoy my day-job writing are inevitably disappointed by the humdrum reality of my actual life, as laid bare by social media.

And if that realisation is jarring for people who follow me on Twitter, I can only imagine how it must feel for people who follow actual celebrities. Take Justin Bieber who this week got into a back-and-forth with some teenagers who claimed, on Twitter, to be at a party organised by him. Bieber shot back by DM: “I didn’t have a party. I don’t know who those girls are. I’m with 6 of my friends and my family…” He couldn’t let it go at that, though, adding: “what are their twitter names… they are liars.” And with that exchange, Justin Bieber – global pop sensation – became Justin Bieber – regular kid on his cellphone, pissed off that people are making shit up about him. He’s just like we were at that age. How dull.

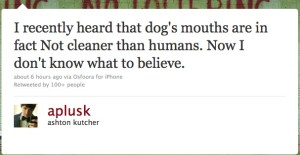

Still, at least Bieber has an excuse for tweeting like a teenage: he is a teenager. Ashton Kutcher on the other hand…

If you’re one of the three people in the world not already following Kutcher (I’m another), then take a moment to browse his latest tweets: with every 140 character nugget, Kutcher becomes less ‘social-media savvy husband of Demi Moore who was in that show once’ and more ‘over-enthusiastic teenager with a cellphone’. The more we know, the less we want to know.

Go a step further. Contrast the hell-raising antics of classic stars like Richard Burton and Oliver Reed, with today’s famous drunks like David Hasselhoff and Lindsay Lohan. Why did the problems of the former only add to their legendary status, while with the latter it only makes us pity them? A difference in acting ability? Well, sure. But mainly it’s because in the case of Burton, Reed et al, fans only read about their heroes misbehavior in newspapers after the fact: stylised accounts of nights spent stumbling out of bars and brawling in the street. With today’s stars, social media – everyone having a camera, and every misstep ending up on YouTube – means that we can actually witness the drunkenness as it happens, or shortly afterwards. That’s never pretty.

Social media allows us to become familiar with people who in a previous life would be unknowable “stars” — and we all know what familiarity breeds. There’s a reason why reality stars fade from the limelight so quickly and why none of the movies on Project Greenlight became a success: to mix a metaphor, you can’t become a star if everyone has seen the sausage being made.

In Esquire, S.T. VanAirsdale argued recently that we’re on the cusp of a rebellion against over-exposed celebrities: that tomorrow’s stars will not be Twitter-whores like Bieber and Gaga but virtual recluses in the mould of Greta Garbo and JD Salinger. If that’s true – that fame and fortune will soon be inversely proportional to social media exposure – then God help someone like me: someone who can only dream of the level of success attained by Salinger or, uh, Bieber.

Not only is my constant lifecasting boring to tears people who actually want to like me but, worse still, I’m spending hours every week dicking around keeping those half-dozen profiles up to date when I could be using the time writing another column, or researching another book. You know, something with the potential to actually make me seem interesting. Something that could – probably won’t, but could – one day make me famous. Quelle ironie.

For that reason, them, as the publication date of my next book approaches, I’ve decided to take precisely the opposite self-promotional strategy to the one I took for the last one. Cue the Social Shutdown: I’ve closed down all of my social media accounts: deleting Foursquare, Plancast, Buzz, Facebook, LinkedIn, Delicious, Blippy and all of the rest.

All, in fact, except Twitter. I was going to axe that too, but then I paused: I really enjoy writing those little 140 character updates, for the amusement of friends and because they occasionally allow me to test-drive jokes and ideas before throwing them out to a wider audience (I have just under 10,000 followers – a big number but considerably lower than the readership of even my least popular TechCrunch post. And a number dwarfed by how many people have read my last book in its various forms).

Twitter, then, might survive the cut – but with one significant change: I’m a couple of hundred followers away from reaching 10,000 and after that I’ve decided to lock my account. (Update: done) Ten thousand is more than enough followers for one person, and it’s a number that will still allow me to have fun with the service – keeping up with friends, testing ideas, responding to amusing @replies – without obsessing about what the wider world will make of my frighteningly mundane life.

So that’s that. Finally social media is put back in its place: a closed way to connect with friends old and new, rather than a sprawling, digital re-incarnation of Seymour’s plant: demanding my constant attention while at the same time plotting my professional demise.

I miss it already. Anyone want to know what I had for lunch?