Ask any old-time IBMer, and you will hear stories of IBM’s legendary workforce-development practices. When a manager identified a manufacturing worker with promise, the company would teach him how to dress, how to speak to clients, and how to service products. These technicians would then be trained to be computer programmers, sales reps, or product managers. IBM president Thomas Watson, Sr., considered education so important that, in 1932, he started a mini-university for employees, the Endicott schoolhouse.

Ask any old-time IBMer, and you will hear stories of IBM’s legendary workforce-development practices. When a manager identified a manufacturing worker with promise, the company would teach him how to dress, how to speak to clients, and how to service products. These technicians would then be trained to be computer programmers, sales reps, or product managers. IBM president Thomas Watson, Sr., considered education so important that, in 1932, he started a mini-university for employees, the Endicott schoolhouse.

That was until the ’70s. IBM still provides good training, but try getting a job there today: unless you have just the right skills, you won’t even score an interview. New recruits don’t receive the year or so of training that was common; they get a few days of orientation, after which they’re expected to be productive. It’s the same at Microsoft, Google, Apple, and almost every tech company. Unless you have the alphabet soup of technologies on your resume, you’ll get nothing more than an auto-response to your job application. If you do get hired, it’s up to you to stay current or get booted out with the first dip in sales. American corporations consider their workforce to be disposable — like ball-point pens and cigarette lighters. Gone are the days when a company would train a factory worker to become a computer programmer or offer lifelong employment. It’s all about quarterly revenue and profits now.

Large corporations do offer some employee training programs, but managers often discourage their workers from participating in them. Why invest in workers when there is no clear payback? After all, training requires time off, and costs the department money. And bosses fear that once their subordinates gain new skills, they will be more likely to jump ship — to a better-paying competitor. That’s the common belief.

But as lessons from the unlikeliest of places show, these assumptions are wrong. Workforce education increases productivity, decreases turnover, and leads to greater corporate growth. I was myself surprised to see this correlation when I researched the secrets of the success of Indian industry.

But as lessons from the unlikeliest of places show, these assumptions are wrong. Workforce education increases productivity, decreases turnover, and leads to greater corporate growth. I was myself surprised to see this correlation when I researched the secrets of the success of Indian industry.

Industry pundits often tout India’s engineering-graduation rates as India’s advantage. As far back as 2002, “experts” claimed that India graduates 350,000 engineers every year. The reality is that India has a weak education system and produces far fewer engineers than is commonly believed. In 2002, it graduated 102,000 engineers. By 2006, this number had increased to 222,000 (and will be double that again, by 2011). India does have some excellent engineering schools, but at best, only half of the output of India’s engineering colleges are employable upon graduation. Yet in 2007, India’s five largest IT services companies added 120,000 engineering jobs. IBM and Accenture added 14,000 engineers each in India in the same year. That’s only seven of the hundreds of companies that hired engineers that year. Where did these engineers come from, and how is it that India’s R&D industry is booming?

My team made several trips to India during 2007 and 2008 and met the executives of dozens of leading companies to solve this puzzle. We also interviewed workers in R&D labs and reviewed the types of work they were doing. We were astonished at what we learned. I’ll explain.

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Japanese achieved major advances in manufacturing management, which led to their rise as an economic power. The Japanese economic miracle and the country’s new manufacturing skills and methods surprised western firms; but the Japanese had done this by studying, adopting, and eventually perfecting the best practices of the West itself.

My research team (at Harvard and Duke) found that India is achieving similar feats in workforce development by learning from the best practices of the western companies that have outsourced their computer systems and call centers there. It has adopted these practices and perfected them. Faced with severe talent shortages; escalating salaries; and a lagging education system, Indian industry had to adapt and has built innovative and comprehensive approaches to workforce training and management. Their initial focus was on training new recruits and filling entry-level skill gaps. Now, they are investing in constantly improving the skills and management abilities of their workers and in providing incentives for them to stay and to grow with the company.

We published a report titled “How the Disciple Became the Guru”, which details the workforce-development practices of 24 leading companies in India (note: there are many bodyshops in India that don’t invest in their people, we looked at the biggest companies). I suggest you download and read this, but I’ll present some highlights here of what the best Indian companies are doing right.

Recruitment: When you’re looking for a job, what’s the first thing you do? Create a good résumé. What does a good résumé tell about a person? Simply the ability to write a good résumé. The résumé doesn’t reflect skill, potential, or aptitude. Indian companies figured this out long ago. So they started putting applicants through batteries of psychometric tests and rigorous interviews. They hire for general ability and aptitude, rather than specialized domain and technical skills. Indian companies also learned to cast a wider net when looking for people with potential. Instead of hiring only from elite engineering colleges, technology companies such as Infosys, HCL, and TCS recruit from second- and third-tier colleges all across the country, and also in arts and science schools. India’s largest call-center operator, Genpact, has set up branded storefronts in 19 cities, where applicants can learn about the company and apply for a job; no resume required.

New-employee training: Companies in India assume that new recruits will have to be trained practically from scratch. So most large companies have built dedicated learning centers, and some employ hundreds of training staff. The Infosys Global Education Centre at Mysore can train 13,500 people at a time. New recruits attend a 16-week boot camp that strengthens their technical, communications, and management skills. For its arts and science recruits, TCS provides an additional three months of training. That’s right: fresh recruits get four to seven months of training before starting work.

Continuing training: Employees are typically required to participate in a wide range of education programs, including not only technical and domain training but also a wide range of soft skills and management skills encompassing training in quality processes; communication; and cultural, foreign-language and personal-effectiveness skills. It is common for companies to mandate one to four weeks of yearly training for employees. That is more than the vacation time that many Americans get. And these workers get rewarded for improving their skills: career advancement and salary increases are usually tied to the completion of training.

Companies don’t just offer online courses. They have programs of mentorship by senior executives; peer learning and knowledge sharing; and job-rotation programs. Take the example of Cadence India. Its CEO, Jaswinder Ahuja, instituted a “leaders as teachers” program under which every manager is required to spend one to two weeks teaching internal classes. Not even the CEO is exempted from this rule. Training is considered so important that the most senior executives do their part. Trainers are often the most skilled and successful employees rather than those who couldn’t cut it in customer engagements.

Managerial development: Managers are typically groomed through fast-track programs that provide management training and mentorship to highly performing employees. Preference is usually given to internal staff to fill management openings. (Yes, many companies have a policy that insiders get first dibs at management jobs). The formal training curricula include project-management, team-building, people-management, communication, coaching, and other managerial skills. On-the-job learning is provided through a variety of structured developmental experiences: job rotations, early managerial responsibilities, cross-functional projects and experiences, and intrapreneurship initiatives.

There was a time when Indian companies were so desperate to hire western-trained and -educated managers that these people would command premium salaries. Today, companies find that they can hire better talent locally. Gone are the big salaries. Returnees to India with too much management experience from abroad can have a hard time even finding a job in India.

Performance management and appraisal: Companies use ERP-like systems to manage the human-development process. Employees usually get reviewed at the end of every project. They are prescribed training if found to have weakness. (Yes, the performance review is used to guide development, rather than to protect the company from lawsuits in case they need to fire you).

Mechanisms such as 360-degree reviews (wherein you review your bosses and peers) and balanced-scorecard reviews are widely used. Managers are evaluated on a variety of non-financial measures, including employee satisfaction, attrition rates, and mentoring.

Where is the proof that these policies work?

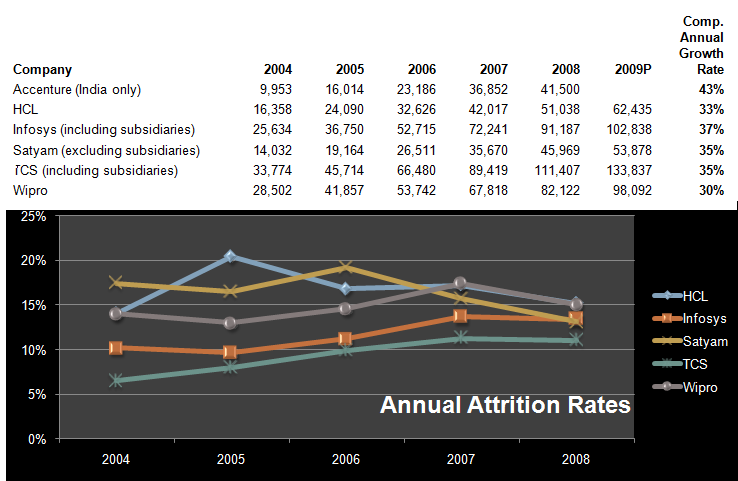

The myth is that Indian IT companies have high turnover that is and getting worse. As the graph below shows, at a time when the Indian IT industry’s growth rates averaged a dizzying 40%, attrition rates at top Indian companies fell, or stayed in the low-teen percentages. Compare this with Silicon Valley, where a typical recruit works for a new employer for three to five years at best — which translates to a 20–33% attrition rate. (Indian IT company rates dropped even further in 2009 — not reflected in the chart).

Most interestingly: Indian companies learned that with better education, employees became more productive so they could afford to pay higher salaries without hurting corporate profit margins.

Additionally, the Indian R&D industry has been moving into the higher realms of innovation. In the aerospace industry, Indian companies are designing the interiors of luxury jets, in-flight entertainment systems, collision-control / navigation-control systems, fuel-inverting controls, and other key components of jetliners for American and European corporations. In pharmaceuticals, Indian scientists are discovering drugs and performing clinical research for nearly all of the largest multinational drug companies. In the automotive industry, Indian engineers are helping to design bodies, dashboards, and power trains for Detroit vehicle manufacturers — and creating their own innovations, such at the Tata Nano car. In telecommunications and computer networking, Indians are developing next-generation infrastructure for tomorrow’s intelligent cities. There are over a hundred thousand people in India doing this type of advanced R&D.

The Indian experience highlights what can be achieved by investing in upgrading the skills of the workforce. If workforce training can take the output of an education system as weak as India’s and turn its graduates into world-class engineers and scientists, imagine what could be done with a worker base that has received amongst the best education in the world, as is the case in the United States.

U.S. companies have long played the guru, developing and disseminating many widely adopted management and workforce practices. The time has come for the guru to learn from one of its disciples: India.