I’ve always had mixed feelings about the DMCA.

I’ve always had mixed feelings about the DMCA.

On the one hand, as an author, I like that it gives me a way to stop illegal copies of my work being distributed in the US, so ensuring that I can continue to make a living without having to get a proper job. On the other hand, as an occasional journalist, I hate that it can also be used by trigger-happy lawyers to prevent certain embarrassing documents entering the public domain.

Thus conflicted, it was with some trepidation that I received news from the old country that Gordon Brown’s government is getting ready to enact its very own version of the DMCA. Called the Digital Economy Bill (DEB), the new statute aims – amongst other things – to halt the rising tide of intellectual property theft on the Internet. But unlike the DMCA, its reach won’t be limited to national borders: any site anywhere in the world that’s accessible from the UK needs to obey the law or else it’s liable to find itself blocked from the entire country. I’m not kidding, this is China-level enforcement.

The bill originated in the House of Lords (our second law-making chamber) where it’s being tweaked and plucked, with various clauses added and removed – before being sent to the Commons (our first chamber) for debate and a final vote. Here in a nut are the key clauses as it currently stands:

Firstly, if the law passes, ISPs will be obliged to keep track of all allegations of illegal file-sharing made by copyright owners. These complaints will be used to produce an list of “persistent offenders” (subscribers who had received more than, say, 50 complaints about them) which will be made available on request to the copyright owners. The list will be anonymised, with subscribers identified only by a reference number, but copyright owners can then apply to the British courts to subpoena the names and addresses of the subscribers involved. Copyright owners can then take legal action directly, claiming substantial damages for each violation. The government is also able to take action: demanding that ISPs cut off internet access from households identified as persistent offenders.

A second – and even more controversial – clause was bolted on by members of the House of Lords in response to the claim that over 35% of copyright breaches occur not through P2P sharing, but rather through media hosts like YouTube and file locker services like Rapidshare. The new amendment will give the courts the power to demand that British ISPs block access to any site that knowingly and unlawfully hosts copyright material. That’s not just sites hosted in the UK but any site anywhere in the world. As with the DMCA, the ISP won’t be liable until they are notified of the illegal content (the ‘safe harbor’ defence) providing they then take immediate steps to block the sites hosting them. If, however, the ISPs refuse to act, they will be liable to the full legal costs of the copyright owner. But unlike the DMCA, the amended bill contains absolutely no penalties for copyright owners who file bogus or spurious claims. The effects are about as chilling as can be: it is in the copyright owners’ interests to make as many claims as they like, and in the ISP’s interests to immediately block every site they’re notified of in order to avoid potentially huge legal costs.

Opponents of the bill point out that most cases will never come to court as ISPs will roll over immediately, as they frequently do under DMCA in the US. But the opponents don’t stop there. Hell, they don’t really stop anywhere. Between the amended blocking clause which could, in theory, see sites like YouTube blocked from the UK – and the potential for having one’s entire house disconnected from the web, the DEB has come in from a veritable gale of criticism, much of it vented right here in the blogosphere. Who’d have thunk it?

TechCrunch’s own Devin Coldewey notes that the “persistent offenders” list won’t just affect domestic file-sharers. Internet cafes, hotels and anywhere else that offers public wi-fi access could find themselves taken offline if their customers are found to be swapping copyright files. If anything, these public access points are even more at risk as it doesn’t take many teenagers using your cafe to rack up 50 copyright violations: this despite there being no way for the establishments to police what their customers are doing online. As Boing Boing’s Cory Doctorow put it, almost entirely without hyperbole, “UK Digital Economy Bill will wipe out indie WiFi hotspots in libraries, unis, cafes”

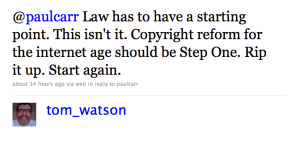

In fact Doctorow is one of the bill’s harshest critics, writing numerous posts about its dangers. Not only is he vehemently opposed to the persistent offenders clause but he also rails against the site-blocking amendment, arguing that it will essentially ban file lockers from the UK, even when much of the content hosted on them is perfectly lawful. In response to Doctorow and his ilk, thousands of UK web users have signed petitions opposing the bill. Even members of parliament have come out to publicly attack the proposed measures – as Tom Watson MP told me on Twitter: “Enshrining net filtering at ISP level scares me half to death…. Law has to have a starting point. This isn’t it. Copyright reform for the internet age should be Step One. Rip it up. Start again.”

A clusterfuck, then. A total shit show, even more draconian than the DMCA and even more packed to the gills with chilling effects. There’s an election coming up in the UK and the government is apparently anxious that the law be pushed through before then, but to do so would be a travesty – instead the bill should be scrapped and revisited in the next parliament.

A clusterfuck, then. A total shit show, even more draconian than the DMCA and even more packed to the gills with chilling effects. There’s an election coming up in the UK and the government is apparently anxious that the law be pushed through before then, but to do so would be a travesty – instead the bill should be scrapped and revisited in the next parliament.

Or at least that was my first thought. Then I actually read the bill.

And, you know what, it’s actually not that bad.

For a start, the first point of contention – the compilation of a persistent offenders list, and the potential banning of them from accessing the Internet – isn’t quite as unfair as it sounds. Despite Doctorow’s claim that “your entire family [can] be cut off from the net if anyone who lives in your house is accused of copyright infringement, without proof or evidence or trial”, there are actually multiple points at which evidence comes into play, and the accused file-swapper is given a chance to defend themselves. The bill requires the creation of an independent tribunal body to hear claims of unfairness arising from the new laws, and alleged infringers have not one but two rights of appeal to the tribunal. With each alleged breach, the new law demands that the ISP send a letter to the subscriber putting the allegations and the evidence to them.

Only once a significant number of breaches have been alledged (the drafters of the bill suggest 50) will the subscriber be added to the persistent offenders list. Again, they will be notified. Only at this point can the copyright owner appeal to the court – using a law that has been around for 36 years – to get the name and address of the offender. Even then, though, they won’t be taken to court. Instead, the copyright owner has to send the subscriber yet another letter (this will be their 52nd) warning them that legal action is imminent if they don’t stop. It’s only then that legal action will be taken, leading to a possible fine and – only at the extreme end of the scale – their Internet access being disconnected.

The second point of contention – the blocking of file-sharing sites – is still pretty bad, but again it’s not quite what some commentators [*cough* Cory *cough*] suggest with headlines like “Lords seek to ban web-lockers (YouSendIt, etc) in the UK“. Yes, the courts will have the power to require ISPs to block sites that egregiously host copyrighted files. But they can only do so if the site involved has refused to remove the copyrighted files – a last resort against foreign file lockers who ignore British court injunctions. More importantly it’s also a power that the British courts have had since the 2002 E-Commerce Directive Regulations (with ISP’s being similarly liable for inaction): the new legislation simply creates a DMCA-style process for making take-down requests easier to issue.

After several hours of reading – not just the proposed new law but also all of the existing copyright law, plus the current World Intellectual Property Organisation Treaty (the UK is a signatory) and also hundreds of pages of discussion around all of the above – a few things became clear…

For one thing, many of those opposing the bill don’t seem to be opposed to the bill itself so much as they’re opposed to the entire notion of copyright law, particularly when it’s used by “greedy record companies” or “rich recording artists”. As one commenter put it on the Guardian: “If you want to be solely a ‘recording artist’ and find you’ve been caught short – tough. No one owes you a living. You’ve been rendered obsolete by technology (not me) and you either adapt or fade away like so many other industries.” The only copyright law that people like that will accept is one that lets them steal whatever they like.

Far be it from me to suggest that Cory Doctorow has an anti-copyright agenda, but there’s no doubt he’s the world’s leading proponent of the ‘give everything away free and reap the tangential rewards’ model of intellectual property protection. Creative Commons might work perfectly for a man who makes his living writing and speaking about how he gives things away free, but it’s not always the answer for musicians, authors and filmmakers who don’t have that particular sideline. And I say that as an author who just gave his last book away under a Creative Commons license and who isn’t going to go broke any time soon.

Whatever Doctorow’s biases, headlines like “UK Digital Economy Bill will wipe out indie WiFi hotspots in libraries, unis, cafes” or “Leaked UK government plan to create ‘Pirate Finder General’ with power to appoint militias, create laws” do nothing to encourage rational debate. In fact, they’re curiously reminiscent of “Obamacare will kill grandma” claims from Republicans in the US. Why debate facts when you can drive people to your way of thinking through scary headlines?

And yet, shrill objections aside, it’s equally clear that the Digital Economy Bill has its fair share of potential problems. There’s not a huge amount of new law in the bill, but there are a whole bunch of new processes – new takedown notices, persistent offender lists etc – all of which will need to work properly from day one. In the British government’s haste to rush it through before the upcoming election, there’s a huge risk of passing a bad statute which will prove impossible to enforce.

Most clear of all though is that, beyond a general call to “scrap the bill and start again” (again: paging the Republicans), none of the opponents of the bill are suggesting a credible alternative. For all of our fears of “chilling effects” the fact is that the Internet is shitting all over the intellectual property rights of the UK creative industries (industries which account for 7.9% of the nation’s GDP). Existing law offers almost all of the protections required by copyright owners, but it’s too slow and costly to enforce in the face of widespread online infringement. A shake-up of the enforcement process is much needed – not just to protect fat cat record companies, but also to ensure the livelihoods of thousands of musicians, authors, filmmakers, photographers, artists and the rest who contribute to our cultural landscape. To those people, the effects of an online copyright free-for-all are just as chilling. If the DEB isn’t the right bill , then it is beholden on those attacking it to suggest an alternative.

Here’s mine:

1) My parents run a business that offers free wi-fi to their customers. I know it’s impossible for them to act as copyright police and so, alarmed by the proposed bill, they’ll likely choose to close down their wi-fi hotspots. To avoid that, the law needs to distinguish between domestic and business internet users when it comes to the persistent infringers clause. For domestic users, the 50-strikes and you’re out clause – and the disconnection threat – should stand: it’s a powerful deterrent, and there are plenty of points at which householders can appeal. For businesses and public wi-fi providers, the disconnection threat should be dropped entirely – it’s clearly a disproportionate punishment – but the fine should remain. In both cases, though, the burden should rest on the copyright owner to prove complicity in the infringement. Domestically, this is as simple as proving multiple breaches from the same IP address – there is a duty on the homeowner to lock down their wi-fi and to know what is happening under their roof, especially after receiving multiple notifications. For businesses, though, the copyright owner should face the (almost impossible) task of showing that the business owner is knowingly permitting copyright breaches on their premises. They’ll basically have to send private detectives round and catch the owner in the act – something only worth doing in extreme cases.

2) The current site-blocking amendment should be dropped entirely. Instead it should be replaced with a virtual carbon copy (quelle irony) of the DMCA’s takedown procedures, but with even more severe punishments for copyright owners who file spurious claims. If an alleged infringer files a counter-notice but the copyright owner decides not to then pursue legal action, the former should be immediately entitled to claim damages against the latter, set at a fixed amount (say £250 – a little under $400) for every day each affected file was offline. In the case of entire sites being blocked, these damages could be enormous. The result: copyright owners will have a costly disincentive against filing spurious claims.

3) Finally, and most importantly, the bill should be abandoned until the next parliament. Rushing through legislation is almost never a good idea – and it’s not like it’s going to be a vote winner, either for this government or the next one. With the full lobbying force of the creative industries behind a new law, there’s virtually no chance that it won’t be passed in the next twelve months so MPs should take the next few months to revise it, to consult with experts, to explain it to critics and generally to ensure that everything that can be done to make it fair has been done.

The UK’s creative industries generate £112.5 billion in revenue for the British economy. The Digital Economy Bill should be passed, and it should be passed soon. But more than all of that, it should be passed right.