With the year—and decade—coming to a close, the business press has been awash with stories about just how lousy the ‘00s were. As Paul Krugman details in the New York Times, it was a decade with a tiny amount of job creation, and the first decade on record where private-sector jobs shrunk. The typical family got no economic boost at all. And when the volatility rollercoaster ended there was also no appreciation in home prices and zero gains on stocks.

With the year—and decade—coming to a close, the business press has been awash with stories about just how lousy the ‘00s were. As Paul Krugman details in the New York Times, it was a decade with a tiny amount of job creation, and the first decade on record where private-sector jobs shrunk. The typical family got no economic boost at all. And when the volatility rollercoaster ended there was also no appreciation in home prices and zero gains on stocks.

That pain was felt by venture capitalists as well. I’ve argued for a while now that once the gains from 1999 and 2000 fall off the ten-year index of VC returns, we’re going to be looking at an industry that has returns at or below the S&P 500. Given we’re coming out of a “decade of zero,” that’s a pretty bad thing. Especially for an asset class that is (supposed to) take huge risks in the name of potentially outsized returns.

Dow Jones VentureSource is releasing its year-end liquidity numbers for 1999 this morning and no surprise—it’s just another data point nail in the coffin.

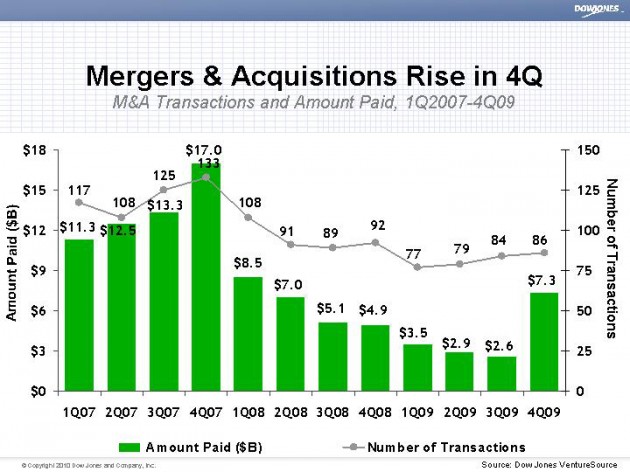

At a high level you can put a good spin on the facts: In the fourth quarter acquisitions rebounded mightily. Public companies snapped up some 86 venture-backed companies for a total of $7.3 billion and three IPOs raised a—let’s be honest—paltry $220 million. And the median amount paid for a company in the fourth quarter was more than $100 million for the first time since 2000.

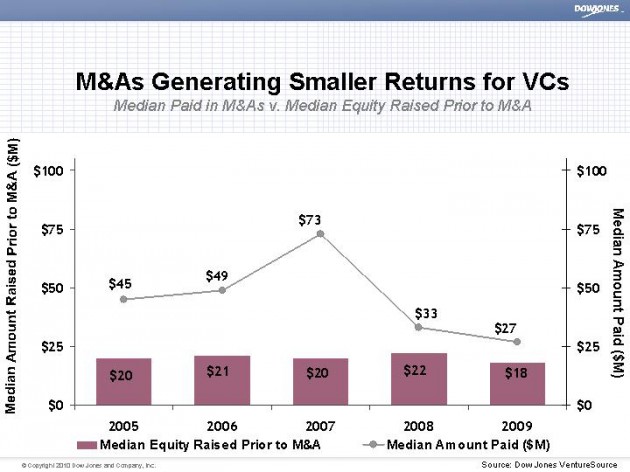

But as frequently happens in quarter-to-quarter surveys, that $100 million number was skewed greatly by a few large deals, most notably, Zappos’s $1.2 billion purchase by Amazon. Overall, for the year the median acquisition price was just $27 million.

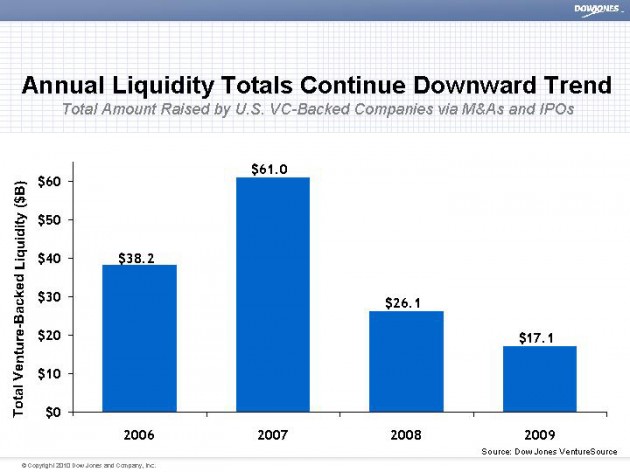

And the overall rebound in fourth quarter liquidity is only impressive compared to the nine months prior. For the year, the industry produced just $17.1 billion in returns, 34% less than the $26.1 billion generated in 2008. And that wasn’t a particularly good year.

The surge in M&A and talk of some promising companies waiting in the wings to go public aside, this industry is in as much trouble as ever for three simple reasons. If these reasons don’t get addressed the 2010s may be worse than the ‘00s for the asset class.

1. The Math Doesn’t Work. An industry that invests roughly $20 billion a year (or even more), can’t survive on returns of roughly $20 billion a year. The basis of a portfolio investing business is that the hits have to make up for the losses—not just pay for themselves. It doesn’t matter how much you believe in innovation, how much you believe in the Valley and how much you believe in venture capital itself—the numbers are now and have for the last decade been hopelessly out of whack. Unless investors can discover an area that can produce many billion-dollar homeruns like the ecommerce, enterprise software and telecom did in decades past, there needs to be dramatically less money investing in early stage firms, period.

As we speak, many once proud venture firms are having a hard time raising their next funds, and many are turning towards less-desirable limited partners out of necessity. A host of funds were supposed to close in 2009 and haven’t yet. Watch the news in 2010 closely: If firms are taking money from state pension funds, raise an eyebrow. Back in the early 2000s state funds came under pressure from Freedom of Information Act requests to divulge information about underlying portfolio investments and privacy-conscious VCs turned their backs on those pension funds as a result. Anyone going back to them now was likely told no by nearly everyone else. Of course, those firms will still be in business. But not all firms will once their current funds are depleted, and ultimately, that’s a good thing for the industry.

2. M&As Alone Will Not Sustain VCs. While it’s true that the bulk of exits VCs get are from acquisitions, this is not where the bulk of returns come from. The economics of venture capital are based on homeruns. That’s why some 5% of the industry makes some 95% of the money. And those big hits come from IPOs or in some cases the threat of an IPO that makes a publicly-held competitor pay a huge premium for a startup. This is why M&A values surged so high in the late 1990s. Companies like Cisco had to shell out hundreds of millions or even billions to buy a company because it was so easy for them to go public. That’s not the case today and when you only have a handful of companies out buying, even a Google or Cisco shopping spree can only net so much in returns.

3. The Perilous Ripple Effect. There is a way that venture capital can adjust to a new normal of smaller exits with smaller multiples: Taking less risk and selling early. That means a switch of focus from building companies to building products. This is how much of the world outside Silicon Valley invests now. The benefit is it requires less capital and less risk. If you build something of value, there’s a likelihood you can get $5 million or even $20 million for it. But that’s the cap of what you’re going to get without a business to back that product up. But that’s OK economically, because you have fewer failures since you’re taking less risk.

Indeed in 2009, Dow Jones found that companies raised a median of just $18 million in venture capital before getting acquired. That’s 18% less than in 2008. And the companies sold faster. It took a median of five years to get an exit, versus six years in 2008.

A lot of entrepreneurs and angel investors argue there’s nothing wrong with this. With far less capital needed to start a company these days, what’s wrong with a smaller exit? You’re still making money, right? Not every idea has to be a $1 billion one to be worth starting.

That’s true for a bootstrapped or angel-funded startup, but not for venture backed deals and the Valley at large. That kind of thinking will eventually destroy an ecosystem that is built on a foundation of homeruns paying for all mistakes. Put another way, the reason we are so famously free to fail in the Valley is that a big homerun can economically make up for those failures. That is what has set Silicon Valley apart for decades. If that changes, the output of the Valley will change too.

And don’t forget: The companies providing these modest exits are the homeruns from previous decades. Without the past big hits of Google, Microsoft, Yahoo and Cisco, who’d be paying $20 million for your Web 2.0 app today? Consider that Facebook—a company that was ridiculed by the press and analysts for not selling for $1 billion or less back in 2006 —has already bid $500 million for Twitter and acquired FriendFeed. Good thing for the Valley Facebook didn’t listen to critics.

You don’t have to look too far to see what a world where VCs only build-to-flip would look like. It’s largely happened already in lifesciences. The industry that gave birth to Genentech, Amgen and a lot of promise for returns, job creation and cures, has now turned into big pharma’s outsourced R&D lab.

I’m not blaming investors. Because of the high costs of clinical trials, biotech companies used to go public to fund clinical trials. But in the post-2000, SarbOx chill it became all-but impossible for pre-clinical trial, pre-revenue companies to go public. That meant the work had to get financed another way, and that other way was licensing deals with big pharma. Unfortunately, that means a lot of the value from those breakthroughs goes to big pharma, all but ensuring the next Genentech or Amgen may never be created.

But tech doesn’t have those costly restrictions. Do we really want to embrace and celebrate an M&A only world of returns anyway?