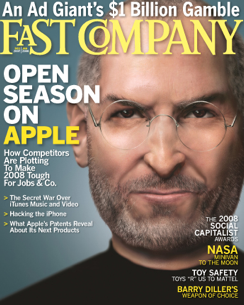

“Merry Christmas, Steve. Enjoy it while it lasts.” That is the sentiment of Fast Company‘s December cover story about Apple, written by Adam Penenberg. (I got my hands on the cover at right, which is a computer-generated image of a sour-faced Jobs by Alex Ostroy). He argues that it is a “dangerous moment for Apple.” The stock is near an all-time high, with a P/E ratio about the same as Google’s. Everyone from Nokia to Amazon to Microsoft to Vivendi Universal to NBC is gunning for it, and its ability to sell 10 million iPhones next year—the famous third leg that is propping the stock up—is yet to be proven. Writes Penenberg:

“Merry Christmas, Steve. Enjoy it while it lasts.” That is the sentiment of Fast Company‘s December cover story about Apple, written by Adam Penenberg. (I got my hands on the cover at right, which is a computer-generated image of a sour-faced Jobs by Alex Ostroy). He argues that it is a “dangerous moment for Apple.” The stock is near an all-time high, with a P/E ratio about the same as Google’s. Everyone from Nokia to Amazon to Microsoft to Vivendi Universal to NBC is gunning for it, and its ability to sell 10 million iPhones next year—the famous third leg that is propping the stock up—is yet to be proven. Writes Penenberg:

But when you get down to it, the Apple phenomenon is as much about fashion as it is about technology. You might say that Steve Jobs is the Marc Jacobs of computers (minus the heroin), betting the house his products will be, season after season, cooler than anyone else’s. Yet fashion is, by definition, fickle. Lose the buzz, and you’ve got trouble. And for the first time in years, there are signs that Apple is not infallible and that Jobs’s reservoir of goodwill with his followers is not bottomless.

I’m not so sure I buy the arguments that Apple has to worry about the cell phone industry getting its act together, or the music industry, or the movie industry, for that matter. We still have not seen much evidence of this, although there’s been plenty of grumbling from all corners. The notion, for instance, that iTunes has anything to worry about from subscription music services is laughable. Rhapsody? Please. It is a great service, but hardly a business threat to the iPod/iTunes juggernaut. Apple should be more worried about free advertising-supported music services that are popping up.

I do agree, however, that the “iPod-iTunes pairing was the product of a historical moment that may never be reproduced.” AppleTV is certainly a bust, and Hollywood bosses will not be the easy marks that the desperate music executives were when iTunes first got started. Penenberg’s strongest argument is that in an era of increasing openness, Apple’s insistence on closed perfection might no longer fly:

What does Steve Jobs know that Albert Einstein didn’t? Einstein posited that a closed system would become stagnant over time. . . . Jobs may have to accept that Apple’s next wave of growth–or energy, as Einstein might have put it–depends on syncing up his products and platforms with those of his competitors.In an age of convergence and simplification, customers are ever more insistent that computers, phones, TV, and music systems work together. For them, being “open” isn’t about sharing patent information or computer code but about compatibility and seamlessness, from the phones in their pockets to the movies playing on their flat screens. . . . Winning outright is a very tall order, of course. It means coming up with a self-contained system so beautifully functional that a critical mass of consumers are willing to enter that world and never leave

It all sounds good. Except that, it has been exactly this closed-world strategy that has worked perfectly for Apple so far. The digital device industry needs a control freak like Jobs to show the rest of us what is possible when everything works as it should. Open systems are great because of their inherent flexibility, but they can also be more chaotic and difficult to manage. The question is whether everyone else can learn from Apple, catch up, and surpass it. And if they do, whether Steve Jobs won’t simply join their parade (at the front, shouting loudly about his new-found open religion) just as it begins to pass by.